|

صادر عن مجلس حقوق الانسان

اصدر

مجلس حقوق الانسان الدولي تقرير عن شهر مارس 2013

حول وضع حقوق الانسان في ما يسمى بـ ايران ، وجاء

التقرير بخمسة ثمانون صفحة تضمن ارقام ومعلومات

تفصيلية عن الحالة الانسانية وما يتعرض له الانسان

من انتهاكات يمارسها النظام الايراني الديكتاتوري

على ابناء الشعوب غير الفارسية والشعب الفارسي ،

وان الحالة في ايران في مجال حقوق الانسان مقلقة

لما فيها من افراط كبير بحق الناشطين السياسيين

وسجناء الرأي وما يتعرضها لها هؤلاء الناشطين من

احكام جائرة وتعسفية تقضي بأعدامهم وممارسة بحقهم

التعذيب المبرح اثناء التحقيقات وسحب الاعترافات

عنوة تحت التعذيب الوحشي وومارستها من خلال اجهزة

خاصة بتعذيب الانسان .

اصدر

مجلس حقوق الانسان الدولي تقرير عن شهر مارس 2013

حول وضع حقوق الانسان في ما يسمى بـ ايران ، وجاء

التقرير بخمسة ثمانون صفحة تضمن ارقام ومعلومات

تفصيلية عن الحالة الانسانية وما يتعرض له الانسان

من انتهاكات يمارسها النظام الايراني الديكتاتوري

على ابناء الشعوب غير الفارسية والشعب الفارسي ،

وان الحالة في ايران في مجال حقوق الانسان مقلقة

لما فيها من افراط كبير بحق الناشطين السياسيين

وسجناء الرأي وما يتعرضها لها هؤلاء الناشطين من

احكام جائرة وتعسفية تقضي بأعدامهم وممارسة بحقهم

التعذيب المبرح اثناء التحقيقات وسحب الاعترافات

عنوة تحت التعذيب الوحشي وومارستها من خلال اجهزة

خاصة بتعذيب الانسان .

التقرير تضمن قضايا عديدة بالاطلاع والوقوف على ما

جاء به لما له من اهمية ، التقرير يكشف عمق القمع

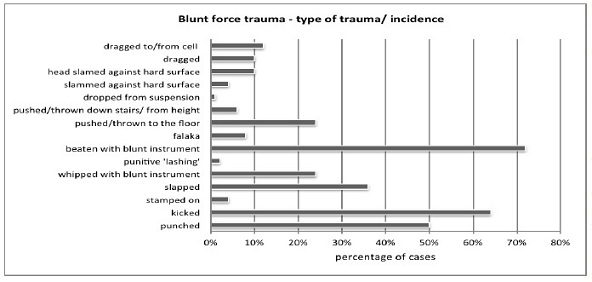

الايراني ومجالاته المختلفة وكلها متعلقة بحياة

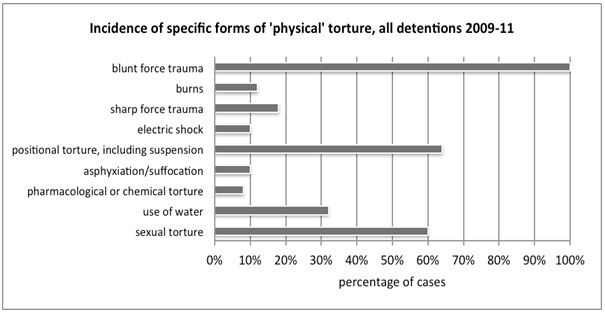

الانسان .

نرفق في هذا الخبر التقرير كاملا بفومات PDF فايل

ويمكنكم الاطلاع عليه او الحصول على نسخة منه عند

الضغط (هنا)

، اليكم بعض ما جاء به باللغة الانجليزية :

[Download Report PDF with Annex]

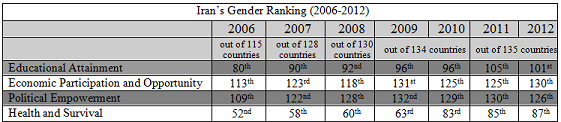

Human Rights Council

Twenty-second session

Agenda item 4

A/HRC/22/56

28 February 2013

Summary

The present report is the second to be submitted

to the Human Rights Council, pursuant to Council

resolution 16/9, and communicates developments

in the human rights situation of the Islamic

Republic of Iran that have transpired since the

submission of the Special Rapporteur’s second

interim report to the 67th session of the

General Assembly (A/67/369) in October 2012.

The present report outlines the Special

Rapporteur’s activities since the Council’s

renewal of his mandate during its 22nd session ,

examines ongoing issues, and presents some of

the most recent and pressing developments in the

country’s human rights situation. Although the

report is not exhaustive, it provides a picture

of the prevailing situation as observed in the

preponderance of reports submitted to and

examined by the Special Rapporteur. It is

envisaged that a number of important issues not

covered in the present report will be addressed

in the Special Rapporteur’s future reports to

the General Assembly and the Human Rights

Council.

Contents

I. Introduction

II. Situation of human rights

A. Free and fair elections

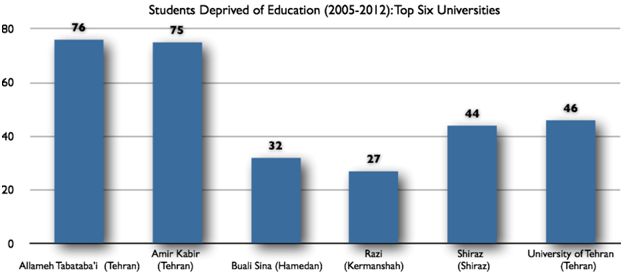

B. Freedom of expression, association, assembly

C. Human rights defenders

D. Torture

E. Executions

F. Women’s rights

G. Ethnic Minorities

H. Religious minorities

I. Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender

community

J. Socioeconomic rights

III. Conclusions and Recommendations

I. Introduction

1. The Special Rapporteur concludes in this

report that there continue to be widespread

systemic and systematic violations of human

rights in the Islamic Republic of Iran. Reports

communicated by nongovernmental organisations,

human rights defenders, and individuals

concerning violations of their human rights or

the rights of others continue to present a

situation in which civil, political, economic,

social and cultural rights are undermined and

violated in law and practice. Moreover, a lack

of Government investigation and redress

generally fosters a culture of impunity, further

weakening the impact of the human rights

instruments Iran has ratified.

2. The Special Rapporteur continues to seek the

cooperation of the Iranian Government in order

to engage in a constructive dialogue and to

fully assess the allegations of human rights

violations. He regrets that it has been not

possible for him to have a more cooperative and

consultative relationship with the Iranian

Government. He communicated his desire to visit

the Islamic Republic of Iran in order to engage

in dialogue and to further investigate the

veracity of allegations of human rights

violations most recently on 9 May 2012. However,

the Government remains reticent on this

engagement and his request.

3. The Special Rapporteur has also collaborated

with a number of other Special Procedures

mandate holders of the Human Rights Council to

transmit three Allegation Letters, 25 Urgent

Appeals, and 7 joint press statements in 2012.

In addition to these communications, he has

written to the Government on two separate

occasions to express his concern about the

ongoing house arrest of opposition leaders, as

well as about restrictions on women's access to

education.

4. The Special Rapporteur has continued to

complement the vast number of reports submitted

by non-governmental organizations and human

rights defenders through interviews with primary

sources located inside and outside the country.

In this regard, 409 interviews have been

conducted since the beginning of his mandate,

169 of which were conducted from September to

December 2012 and submitted for this report.

5. Furthermore, the Special Rapporteur wishes to

report two reprisal cases that have been

reported in the media in November and December

2012, in accordance with resolution 12/2, which

called on representatives and mechanisms to

report on allegations of intimidation or

reprisal.[1] In one case, three Afghan

nationals, Mr Mohammad Nour-Zehi, Mr Abdolwahab

Ansari, and Mr Massoum Ali Zehi, were reportedly

tortured and threatened with hanging for

allegedly submitting a list of executed Afghans

to the Special Rapporteur.[2]

6. Other reports have maintained that five

Kurdish prisoners located in Orumiyeh Prison, Mr

Ahmad Tamouee, Mr Yousef Kakeh Meimi, Mr

Jahangir Badouzadeh, Mr Ali Ahmad Soleiman, and

Mr Mostafa Ali Ahmad, have been charged with

“contacting the office of the Special

Rapporteur” “reporting prison news to human

rights organisations,” “propaganda against the

system inside prison,” and “contacting Nawroz

TV”.[3] The prisoners were reportedly detained

in solitary confinement for two months,

interrogated about contact with the Special

Rapporteur, and severely tortured for the

purpose of soliciting confessions about their

contact with the Special Procedure.

7. The Special Rapporteur is alarmed by these

reports and joins the Human Rights Council and

Secretary-General in condemning “all acts of

intimidation or reprisal against individuals

that cooperate with the human rights

instruments.”[4] He wishes to emphasize the

right of individuals to cooperate with the human

rights mechanisms of the United Nations, and

underscores the fact that such cooperation is

integral to their ability to fulfill their

mandates.

8. The Special Rapporteur takes note of the

Islamic Republic of Iran’s general observations

on the present report[5], appreciates engagement

through such responses, and continues to hope

for direct engagement, as these observations

should not preclude such cooperation. Comments

forwarded by the Iranian government primarily

express concern over (a) the Special

Rapporteur’s working methodology; (b) the

credibility of his sources of information; (c)

his assertions about the Government’s

cooperation with the human rights mechanisms;

and (c) his conclusions that allegations of

violations of human rights reported to him

demonstrate a need for Government investigation

and remedy.

9. The Special Rapporteur has outlined his

methodology on several prior occasions, and

asserts the highest standards of both rigor and

consistency in its application at all times. He

notes that evidence and testimonies submitted to

him have been assessed for compliance with the

non-judicial evidentiary standards required of

his mandate, that sources are cited

appropriately and copiously, whenever possible,

that only allegations that are cross-verified

and consistently leveled by various sources are

presented, and that his findings are in full

compliance with protocol stipulated by the UN

system. Names of sources are omitted whenever

requested, as required by the Special

Rapporteur’s Code of Conduct.

10. Furthermore, the Special Rapporteur has

referenced periodic reports recently submitted

to the treaty bodies by the Iranian government

throughout his report, but maintains that

participation or pledges made in such fora do

not on their own substitute for concretely

addressing and rectifying concerns raised by the

human rights instruments. He also continues to

underscore the fact that despite its standing

invitation, several requests to visit the

country remain outstanding, and that no visit

has been granted to any Special Procedure

mandate-holder since 2005.

II. Situation of human rights

A. Free and fair elections

11. The Special Rapporteur recalls Human Rights

Committee General Comment No. 25, which states

that article 25 of the International Covenant on

Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) “recognises

and protects the right of every citizen to take

part in the conduct of public affairs, the right

to vote and to be elected and the right to have

access to public service.”[6] The right shall be

enjoyed and ensured without unreasonable

restrictions. Any conditions on this right must

be “based on objective and reasonable criteria”

without distinction of any kind, including race,

gender, religion, and political or other

opinion.[7] The Special Rapporteur is concerned

that significant and unreasonable limitations

placed on the right of Iranian citizens to stand

for Presidential office undermine their right to

“participate in the conduct of public affairs

through freely chosen representatives” who “are

accountable through the electoral process for

their exercise of that power”.[8]

12. The Iranian Government reported that under

its Constitution, candidates for the office of

President must be “political-religious men” and

faithful believers in the “foundation of the

Islamic Republic of Iran and official religion

of the country”.[9] Women are therefore excluded

from the Presidency and no female candidate has

been approved by the Guardian Council in the 34

years of the Islamic Republic of Iran. The

Iranian Constitution also deprives citizens who

hold political opinions contrary to that of the

Islamic Republic of Iran and the country’s

official religion of the right to stand for

President. The General Comment on article 25 is

clear that “political opinion may not be used as

a ground to deprive any person of the right to

stand for election”.[10]

13. On 11 February 2013, the Special Rapporteur

joined the Chair-Rapporteur of the Working Group

on arbitrary detention and the Special

Rapporteur on freedom of assembly and

association in a statement urging the Iranian

government to immediately and unconditionally

release former 2009 Presidential candidates Mr.

Mehdi Karoubi and Mr. Mir Hossein Mousavi, his

wife Zahra Rahnavard, and hundreds of other

prisoners of conscience who remain in prison for

peacefully exercising their rights to freedom of

opinion and expression, or freedom of

association and assembly during protests

following the 2009 Presidential election. The

Special Rapporteurs underscored the fact that

the two opposition leaders have not been charged

with a crime since their arrest, and that in its

August 2012 Opinion, the Working Group on

arbitrary detention confirmed that Mr Mousavi

and Mr Karoubi, are subject to arbitrary

detention by the Iranian Government contrary to

article 9 of the ICCPR.[11] In the case of Mr

Mousavi and Mr Karoubi it was reported that the

Iranian Chief Prosecutor suggested that the

opposition leaders repent and make full

restitution for transgressions against the

Government and State in order to participate in

the 2013 Presidential election.[12]

14. The Special Rapporteur is further concerned

that the Iranian Government has not established

an independent electoral authority as indicated

in General Comment 25 “to supervise the

electoral process and to ensure that it is

conducted fairly, impartially and in accordance

with established laws which are compatible with

the Covenant”. [13] He is also concerned about

the availability of information and materials on

voting in minority languages in Iran.[14]

Lastly, the Special Rapporteur recalls, more

broadly, that freedom of expression, assembly

and association “are essential conditions for

the effective exercise of the right to vote and

must be fully protected”.[15] Reports of

statements by Iranian officials issuing warnings

against those citizens who call for a ‘free

election’ and suggesting these calls are

conspiratorial and inimical to the Iranian State

or the principle of velayat-madari (obedience to

the Supreme Leader)[16] undermine the full

enjoyment of article 25 which requires “the free

communication of information and ideas about

public and political issues between citizens,

candidates and elected representatives”.

B. Freedom of expression, association, assembly

1. Journalists and netizens

15. The Special Rapporteur remains concerned

over the continued arrest, detention, and

prosecution of dozens of journalists and

netizens under provisions in Iran’s 1986 Press

Law, which contains 17 categories of

“impermissible” content. The Special Rapporteur

joined the independent expert on freedom of

opinion and expression, human rights defenders,

and the Chair-Rapporteur of the Working Group on

arbitrary detention on 4 February 2013 in

calling on Iran to immediately halt the recent

spate of arrests of journalists and to release

those already detained following the arrest of

at least 17 journalists, the majority of whom

work for independent news outlets. The group of

human rights experts underscored their fear that

the 17 arrests carried-out were part of a

broader campaign to crack-down on independent

journalists and media outlets, under the

accusation that they have collaborated with

‘anti-revolutionary’ foreign media outlets and

human rights organisations.

16. Prior to the aforementioned arrests, 45

journalists were detained in Iran.[17] All five

journalists interviewed about their arrests and

prosecution for this report maintained that they

did not face public trials-by-jury, in

accordance with the country’s Press Law. Two

journalists reported that they were arbitrarily

detained without charges and without ever facing

a trial; one journalist was allegedly detained

for several months and finally released with a

verbal warning, and the other was reportedly

detained for three years, without charges or a

trial, and were finally released on bail. Two

female journalists also reported serious sexual

harassment while in detention.

17. Furthermore, netizen Mr Mehdi Khazali began

serving a 14-year sentence for criticising the

Government on his freelance blog in October

2012; Mr Alireza Roshan, a reporter for the

reformist Shargh publication began serving a

one-year prison sentence in November 2012; Ms

Zhila Bani-Yaghoub, editor of the Iranian

Women’s Club website, began serving a one-year

term on charges of “propagating against the

system” and “insulting the president”, and her

husband, journalist Mr Bahman Ahmadi Amouee, is

serving a five-year sentence on “anti-state

charges”.[18]

18. The Special Rapporteur also remains

concerned by reports detailing the harassment of

family members of journalists who live and work

abroad. In a public statement, 104 journalists

called for an end to the harassment and

intimidation of their family members for the

purpose of placing pressure on journalists to

discontinue their work with such news agencies

as BBC Persian, VOA, and Radio Farda. One

journalist interviewed for this report, for

example, maintained that the passports of two of

her family members were confiscated, and that

the family was threatened with the seizure of

its property if the journalist persisted with

her work.[19]

2. Human rights defenders

19. Interviews continue to impart that human

rights defenders are subjected to harassment,

arrest, interrogation, and torture, and that

they are frequently charged with vaguely-defined

national security crimes.[20] A preponderance of

human rights defenders interviewed for this

report maintained that they were arrested in the

absence of a warrant, and subjected to physical

and psychological duress during interrogations

for the purpose of soliciting signed and

televised confessions. A majority of

interviewees reported that they were kept in

solitary confinement for periods ranging from

one day to almost one year, were denied access

to legal counsel of their choice, subjected to

unfair trials, and in some cases, subjected to

severe physical torture, rape (both of males and

females, by both male and female officials),

electro-shock, hanging by hands or arms, and/or

forced body contortion.

20. In April 2012, Ms Narges Mohammadi, a

co-founder of the Centre for Human Rights

Defense (CHRD), founded by Nobel Peace Prize

Winner Ms Shirin Ebadi, began to serve a

six-year prison sentence for “assembly and

collusion against national security”,

“membership in the Center for Human Rights

Defenders”, and “propaganda against the

system.”[21] It was reported that Ms. Mohammadi

was arrested and taken to Evin Prison, where she

was held in solitary confinement for days. On 11

June 2012, Ms. Mohammadi was transferred,

without explanation, to an unsegregated ward in

Zanjan Prison. Ms. Mohammadi suffers from

muscular paralysis[22] and seizures, and was

released on 31 July 2012 on medical furlough.

However, her sentence remains in place and she

can therefore be re-incarcerated at any time.

3. Lawyers

21. The Special Rapporteur continues to share

the International Bar Association’s concerns

regarding the erosion of the independence of the

legal profession and Bar Association in the

Islamic Republic of Iran.[23] Legislative action

such as the approval of the draft Bill of Formal

Attorneyship, which increases Government

supervision over the Iranian Bar Association, is

a case-in-point. The Special Rapporteur is also

concerned by article 187 of the Law of the Third

Economic, Social and Cultural Development Plan,

which has created a parallel body of lawyers

known as “Legal Advisors of the Judiciary”.

While the law has seemingly increased the number

of legal professionals in the country, partly

through a less onerous licensing process, the

Judiciary ultimately controls the licensing

process of all article 187 legal advisors. The

Special Rapporteur has also received reports

about the revocation of the licenses of article

187 legal advisers after they represented

prisoners of conscience.

22. Furthermore, the Law on Conditions for

Obtaining the Attorney’s License allows Bar

members to elect members of their Board of

Directors, but requires the Supreme Disciplinary

Court for Judges, a body under the Judiciary’s

authority, to confer with the Ministry of

Intelligence, the Revolutionary Court and the

Police to vet potential candidates for its

Board. Some Iranian lawyers have reported that,

in practice, candidates who represent human

rights defenders have been prohibited from

seeking Board membership as a result.

23. The Special Rapporteur continues to be

alarmed by reports of Government action

targeting lawyers. It is estimated that some 40

lawyers have been prosecuted since 2009, and

that at least 10 are currently detained,

including Mr. Abdolfatah Soltani, and Mr

Mohammad Ali Dadkhah. Mr Soltani was arrested in

September 2011 and is currently serving a 13

year prison sentence. On 29 September 2012, Mr

Mohammad Ali Dadkhah, a lawyer and co-founder of

the CHRD was summoned to Evin Prison’s Ward 350

to serve a nine-year sentence after being

convicted of “membership in an association

seeking the overthrow of the Government” and

“spreading propaganda against the system through

interviews with foreign media”.[24] Mr. Dadkhakh

was one the attorneys for Pastor Youcef

Nadarkhani, who was exonerated and released from

prison weeks earlier after being placed on trial

for apostasy.

24. On 17 October 2012, Ms Nasrin Sotoudeh, a

human rights defender and lawyer, who has been

imprisoned since September 2010, began a hunger

strike to protest restrictive conditions placed

on members of her family, including a travel ban

placed on her 12-year-old daughter in June 2012.

Ms Sotoudeh has defended, among others, Shirin

Ebadi. She ended her hunger strike on 4 December

2012 when the travel ban was lifted. Ms Sotoudeh

was temporarily released on a three day leave on

17 January 2013 to see her family, allegedly

with a promise of extending her leave into a

longer or permanent release. She was

subsequently returned to Evin Prison on 21

January 2013. [25]

D. Torture

25. The Special Rapporteur expressed concern

about reports of widespread use of torture in

his report to the 67th session of the General

Assembly. He further reported that 78% of

individuals who reported violations of their due

process rights also reported that they were

beaten during interrogations for the purpose of

soliciting confessions, that their reports of

torture and ill-treatment were ignored by

judicial authorities, and that their coerced

confessions were used against them despite these

complaints.

26. In response to this report, the Iranian

government maintained that allegations of

torture in the country are baseless since the

country’s laws forbid the use of torture and the

use of evidence solicited under duress. However,

the Special Rapporteur continues to maintain

that the existence of these legal safeguards

does not in itself invalidate allegations of

torture, and does not remove the obligation to

thoroughly investigate such allegations. He

further emphasises that widespread impunity and

allegations of the use of confessions solicited

under duress as evidence continue to contribute

to the prevalence of torture.

27. On 15 November 2012, the Special Rapporteur

joined the Special Rapporteurs on extrajudicial,

summary or arbitrary executions, torture and

other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or

punishment and on the promotion and protection

of the right to freedom of opinion and

expression in calling on the Government to

investigate the death of Iranian blogger, Mr

Sattar Beheshti. Mr. Beheshti was reportedly

arrested by the Iranian Cyber Police Unit on 30

October 2012 on charges of "actions against

national security on social networks and

Facebook.” His family was reportedly summoned to

collect his body seven days later. During an

interview for this report, an informed source

communicated that Mr. Beheshti was tortured for

the purpose of retrieving his Facebook user name

and password, that he was repeatedly threatened

with death during his interrogation, and that he

was beaten in the face and torso with a baton.

The source also stated that Mr. Beheshti

reported chest pain to other prisoners and that

authorities were made aware of his complaints,

but no action was taken. A domestic report

released in January 2013 by the Majles' National

Security and Foreign Policy Commission

criticized the Tehran Cyber Crimes Police Unit

for holding Mr. Beheshti in its own

(unrecognised) detention center, but fell short

of alleging direct wrongdoing in his death or of

calling for an investigation into the apparent

widespread maintenance of illegal detention

centers, operated by branches of Intelligence

services, in contravention of Iranian law.[26]

28. The Special Rapporteur is further troubled

by media reports that the memorial service for

Mr. Beheshti was raided by security agents who

beat and arrested members of his family, as well

as a number of attendees. It was further

reported that five security officers beat and

dragged Mr. Beheshti’s elderly mother by her

hair, and that his brother, Asghar Beheshti, was

also arrested and detained for two hours.[27]

29. It was also reported that in late October

2012, the home of Jamil Sowaidi was raided, and

that he was detained by plainclothes officers

claiming to be members of the Islamic

Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC). Frequent

attempts by Mr. Sowaidi’s family to inquire

about his whereabouts were reportedly rebuffed

by authorities. On 6 November, authorities

reportedly confirmed that Mr. Sowaidi had died

in custody and advised his family not to pursue

the case. The family’s request for an autopsy

was reportedly denied, and Mr. Sowaidi was

buried on 8 November 2012. The Special

Rapporteur strongly urges the Government to

conduct a comprehensive and transparent

investigation into Mr. Sowaidi’s death, and

encourages it to take measures to remedy the

matter, in accordance with international

standards.[28]

30. Of the 169 interviews conducted for this

report, 81 cases of reported detention were

examined for allegations of torture. It was

found that approximately 76% of interviewees

reported allegations of torture; 56% reported

physical torture, including rape and sexual

abuse; and 71% of those interviewed reported

psychological torture. In an effort to further

investigate the methods of torture reported by

interviewees, the Special Rapporteur examined a

study on Iran performed by one of the world’s

largest torture treatment centres, which

investigates and forensically documents evidence

of torture in accordance with Istanbul Protocol

standards.[29] Data collected was both

quantitative and qualitative, detailing “history

of detention, specific torture disclosures and

the forensic documentation of the physical and

psychological consequences of torture.”[30] The

medical-legal evidence presented in this study

appears to be consistent with a substantial

number of statements submitted to the Special

Rapporteur in which allegations of torture were

reported.

31. The study examines 50 of some 5,000

documented cases of torture reported by Iranians

to the centre since 1985. Twenty-nine of the

individuals whose cases were examined for this

study were detained in 2009, 14 in 2010 and

seven in 2011. Fifty-six percent of the cases

were detained only once in 2009-2011, while 44%

were detained more than once and up to three

times before leaving Iran.

32. The study concluded that methods of physical

torture described in the 50 cases included:

“blunt force trauma including beating, whipping

and assault” (100% of cases). The study found

that the “main forms of blunt force trauma

consisted of repeated and sustained assault by

kicking, punching, slapping and of beatings with

a variety of blunt instruments including

truncheons, cables, whips, batons, plastic

pipes, metal bars, gun butts, belts and

handcuffs. People reported being assaulted or

beaten on all parts of the body, though most

commonly on the head and face, arms and legs and

back. Most were blindfolded while beaten and

many were restrained, meaning they were unable

to defend or protect themselves.”

33. The study further found the following

methods of torture prevalent among the cases

reviewed: sexual torture including rape,

molestation, violence to genitals and

penetration with an instrument (60% of cases);

suspension and stress positions (64%); use of

water (32%); sharp force trauma including use of

blades, needles and fingernails (18%); burns

(12%); electric shock (10%); asphyxiation (10%);

and pharmacological or chemical torture (8%). Of

the cases sampled, 60% of females and 23% of

males reported rape.”

E. Executions

34. The Special Rapporteur continues to be

alarmed by the escalating rate of executions,

especially in the absence of fair trial

standards, and the application of capital

punishment for offences that do not meet “most

serious crimes” standards, in accordance with

international law. This includes alcohol

consumption, adultery, and drug-trafficking. It

has been reported that some 297 executions were

officially announced by the Government, and that

approximately 200 “secret executions” have been

acknowledged by family members, prison

officials, and/or members of the Judiciary,

making a likely total of between 489 and 497

executions during 2012.[31]

35. It has been reported that at least 58 public

executions were carried out this year. The

Special Rapporteur joins the High Commissioner

for Human Rights in condemning the use of public

executions “despite a circular issued in January

2008 by the head of the judiciary that banned

public executions”. He also joins the

Secretary-General’s view that “executions in

public add to the already cruel, inhuman and

degrading nature of the death penalty and can

only have a dehumanising effect on the victim

and a brutalising effect on those who witness

the execution.”[32] The Special Rapporteur also

remains concerned that provisions in the new

Penal Code, while not yet adopted, seemingly

broaden the scope of crimes punishable by death.

36. On 22 October 2012, Mr Saeed Sedighi, a

Tehran-based shop-owner, was executed along with

nine others on drug-trafficking charges,[33]

despite calls on 12 October 2012 by three

Special Procedures mandate holders to halt the

executions.[34] The Government has yet to

respond to due process-related queries,

including to allegations that Mr. Sedighi was

not permitted adequate access to a lawyer or

allowed to defend himself during his trial.

These rights are guaranteed by article 14 of the

ICCPR, as well as articles 32 and 34-39 of the

Iranian Constitution and by the country’s Law of

Respecting Legitimate Freedoms and Citizenship

Rights (2004), which determines criminal

procedure and defines fair trial standards.

F. Women’s rights

37. Reported statistics demonstrate that the

Islamic Republic of Iran has made remarkable

advances in literacy, access to education for

women, and women’s health during the past 30

years. Literacy and primary school enrollment

rates for women and girls are estimated at more

than 99% and 100% respectively, and gender

disparity in secondary and tertiary education is

reportedly almost nonexistent.[35] Statistics

also indicate that women have experienced

improved access to primary health care. The

maternal mortality rate is estimated at 24.6

maternal deaths per 100,000 live births, and

skilled attendance during delivery is 94.5

percent; which places Iran in the “on track”

category towards the MDG to improve maternal

health.[36]

38. Moreover, the country’s 5th National

Development Plan (NDP) calls for “focusing on

the needs and the creation of constructive

opportunities for women and youth”. The NDP also

refers to principles of equal pay for women and

the expansion of social support for “ensuring

equal opportunities for men and women and

empowerment of women through access to suitable

job opportunities”.[37] Several programs aimed

at advancing these goals have reportedly been

developed, including a scheme to generate “at

home” employment for women. The Chairman of the

Parliament’s (Majlis) Health and Treatment

Commission also recently announced the extension

of maternity leave from six months to nine

months, along with two weeks’ mandatory leave

for fathers.[38]

39. Gender-based disparities in economic

participation and political empowerment remain

problematic however, and some recent

developments threaten to reverse the

aforementioned achievements in education.[39]

These include unsuccessful legislative attempts

to reinforce polygamy and reduce work hours for

women, as well as current policy proposals that

discriminate against women in education and

further limit their civil rights, which are

discussed below.

World Economic Forum: The Gender Gap Reports:

2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012[40]

1. International obligations

40. In 1993, the Committee on Economic, Social

and Cultural Rights (CESCR) noted that Iran’s

obligation to ensure equal opportunity for women

warranted particular attention, especially in

relation to the rights to education, work, and

family related rights. In 2006, authorities

partially agreed to the implementation of

recommendations made by the Special Rapporteur

on violence against women following her visit to

the country. This includes the agreement to

reform discriminatory provisions in the

country’s penal and civil laws, especially with

regard to women’s equal rights in marriage and

access to justice. In February 2010, the Iranian

Government also received and accepted eight of

the 13 recommendations that relate to women’s

rights during the Universal Periodic Review

(UPR).

41. In its second periodic report to the CESCR,

which will be reviewed during the Committee’s

50th session in April/May 2013, the Iranian

Government discussed its program to revise

“existing rules and regulations” with an aim to

advancing women’s participation, raising public

awareness about their “qualifications”, and

enhancing their skills.[41] The Government also

maintained that women’s affairs have received

“special attention in the economic, social,

cultural and political development plans of the

country”, commensurate with its view that “men

and women equally enjoy the protection of the

law, and enjoy all human, political, economic,

social, and cultural rights, in conformity with

Islamic criteria”.[42] In qualifying this

position, Government representatives have

asserted that while it is believed that “men and

women are equal in human dignity and human

rights, this is not to be confused with equating

men and women’s role in family, society, and in

the development process”.[43]

42. This viewpoint is further elaborated upon in

Iran’s “Charter on Women’s Rights and

Responsibilities; adopted in 2004. According to

its preamble, the Charter was developed in line

with the view that “there are various traditions

and perspectives regarding women’s rights based

on their different cultures”. The Charter,

therefore, specifies those rights the Government

believes belong to both genders, and emphasises

those rights it asserts to be specific to women

based on their “physical and psychological”

differences.[44]

43. In light of this viewpoint, the Special

Rapporteur joins the statement transmitted by

the Special Rapporteur in the field of cultural

rights, Ms. Farida Shaheed, which asserts that

while the tendency to view culture as an

impediment to women’s rights is “both over

simplistic and problematic”, “many practices and

norms that discriminate against women are

justified by reference to culture, religion and

tradition”.[45] In this respect, the Special

Rapporteur maintains that the aforementioned

emphasis on gender roles places limitations on

the Iranian Government’s obligation to protect

women’s full enjoyment of their civil,

political, social, cultural, and economic

rights. He asserts that this view arbitrarily

qualifies the degree to which women may enjoy

these rights as that which the Government

perceives to be in conformity with Islamic

criteria. The Special Rapporteur further

maintains that this particular argument

undermines the notion of universal rights, and

compromises the rights protected by the ICCPR

and the ICESCR for virtually half of the Iranian

population.

2. Socioeconomic rights

44. The educational attainment of Iranian women

is not yet reflected in their current economic

status. Statistics demonstrate that a

significant gender disparity continues to exist

in their participation in the labor market, and

women still only occupy a small percentage of

senior managerial positions. It was reported

that compared to the global labour force, 52%,

only 32% of Iranian women are actively engaged

in the labour market, compared to 73% of

men.[46]

45. The Special Rapporteur maintains that

certain legal limitations placed on women’s

employment, coupled with recent revisions of

laws that impact their socioeconomic rights,

severely weaken the Government’s ability to

promote gender equality and to make progress on

those recommendations communicated by the CESCR

in 1993, and during the 2010 UPR. These

limitations include Article 1117 of Iran’s Civil

Code, which provides men with the right to

legally prohibit their wives from engaging in

work outside the home if they can prove that the

work is incompatible with the family’s

interests. It was reported that members of the

Majlis recently proposed four articles that

require women to be married in order to become

members of a university’s scientific committee,

or to be employed at the Ministry of Education

and Training. The speaker of the Parliament’s

Social Commission reported that the

preconditions have not yet been approved.[47]

46. In June 2012, the Science and Technology

Ministry announced that women sitting for the

national entrance exam would be prohibited from

enrollment in 77 fields of study at 36 public

universities across the country.[48] It was

reported that female enrollment in hundreds of

courses offered during the 2012-2013 academic

year at Iranian public universities was

substantially restricted, including in courses

on petroleum engineering, data management,

communications, emergency medical technology,

mechanical engineering, law, political sciences,

policing, social sciences, and religious

studies. [49] Furthermore, policies to enforce

gender segregation provide “single-gendered”

university majors for alternating semesters in

lieu of entirely banning access to either male

or female candidates.[50] In response to

criticism from Iranian parliamentarians who

called for an explanation, the Science and

Higher Education Minister responded that 90% of

degrees still remain open to both sexes, that

single-sex courses were needed to create

“balance”, and that “some fields are not very

suitable for women’s nature”. In light of Iran’s

international obligations under the ICESCR and

the country’s Constitution, the Special

Rapporteur urges the Government to review

policies that could be discriminatory and set

back the progress it has achieved in women’s

education.

3. The right to freedom of movement

47. A married woman may not obtain a passport or

leave the country without her husband’s written

permission. In November 2012 the Chair of the

Parliament’s (Majlis) National Security and

Foreign Policy Commission announcedan amendment

to the country’s passport laws that would

require unmarried women under age 40 and males

under the age of 18 to acquire the consent of

their guardian or the ruling of a sharia judge

in order to acquire a passport.[51] Although

this amendment was finally rejected, it was

reported that the National Security and Foreign

Policy Commission of the Parliament (Majlis)

announced further amendments to the passport

bill which would continue to allow single women

over the age of 18 to obtain a passport without

the aforementioned permission, but would now

require them to obtain permission from their

father or guardian from the paternal line in

order to leave the country.[52]

48. In defence of the amendments, the Chair of

the Parliament's (Majlis) National Security

Commission reportedly stated that the Government

frequently receives requests by single women to

travel outside of the country, particularly for

pilgrimage, and that this prompted the

Government to institute policies that would

ensure their health and safety .[53]

4. Civil and political rights

49. It has been reported that women’s rights

activists continue to be harassed for making

statements that criticise policies or Government

actions; organisational meetings continue to be

disbanded; the denial of permits required to

peacefully assemble persist; and women believed

to be associated with entities such as the

Mourning Mothers and the One Million Signatures

Campaign continue to face harassment, arrest,

and detention. Women’s rights advocates are

frequently charged with national security crimes

and “propaganda against the system”.

50. Activists are also reportedly subject to

travel bans and other forms of suppression for

protected activities, and Women’s rights

activist and member of the “One Million

Signatures Campaign for Equality” Ms Maryam

Behraman was recently sentenced to an

eight-month suspended jail term on the charge of

“propagation against the state.” She was

acquitted on charges of “insulting the leader”

and “founder of the Islamic Republic of

Iran”.[54] Ms. Behraman was arrested on 11 May

2011 in Shiraz on charges of “acting against

national security”, a charge apparently linked

to her participation in the 55th session of the

United Nations Commission on the Status of Women

(UNCSW) in March 2011, and detained for 128 days

in Shriz's intelligence detention center. On 15

September 2011, she was released on $ 300,000

bail. Ms. Behraman’s lawyer reportedly stated

that she had the opportunity to read eight

volumes of her case file and was allowed to take

notes, and submit her defense during the three

relatively lengthy [court] sessions.[55]

51. Furthermore, a number of Iranian laws

continue to discriminate against women. Article

1108 of the Iranian civil code, for example,

compels a woman’s obedience to her husband.

Furthermore, women cannot transfer nationality

and citizenship to their husbands or children,

which has rendered stateless thousands of

children of Iranian women who have married

Afghan or Iraqi refugees, as well as expatriate

Iranian women married to non-Iranians.

52. A dearth of female representation in

decision-making roles remains problematic for

women’s participation in public life, as

guaranteed by Article 25 of the ICCPR. Women are

allowed to serve as legal counsellors, for

example, but are prohibited from issuing and

signing final verdicts.[56] Also, no woman has

ever been appointed to the Council of Guardians

and the Expediency Council. Furthermore, only

nine of the 490 women that reportedly presented

their candidatures for the March 2012

parliamentary elections were elected, giving

women only 3.1% of the 290 seats in the Majlis;

albeit up from eight female representatives in

the last parliament.[57] Prior to the election,

Iranian women’s groups called on the Speaker of

the Parliament to improve female representation

in the Majlis, citing the “increasing number of

professional women; the importance of

incorporating the female outlook on issues in

decision-making bodies; addressing women's and

family issues; and eliminating legal vacuums” as

reasons for their request.[58]

G. Ethnic Minorities

1. Ahwazi Arabs

53. The Special Rapporteur continues to be

disturbed by reports from members of the Arab

community regarding arrests, detentions, and

prosecutions for protected activities that

promote social, economic, cultural, linguistic

and environmental rights. A majority of

interviewees reported that they were arrested in

the absence of a warrant, and that they were

ill-treated during their arrests. Interviewees

maintained that they were detained without

charges for periods ranging from several days to

several weeks Several individuals reported being

psychologically and physically tortured during

their interrogations, including by floggings,

beatings, and being made to witness executions,

threats against family members, and the actual

detention of family members for the purpose of

implicating others, or to compel others to

report to the authorities.

54. One interviewee reported that his/her

cousin, nephew and brother were arrested in June

2012 for the purpose of coercing their children,

who are currently living abroad, to return to

the country. He/she maintained that Ministry of

Intelligence officers reportedly arrested,

detained, and interrogated his/her family

members about possible foreign contacts on a

daily basis for over two weeks in the absence of

charges. They were reportedly subjected to

psychological and physical torture, including by

flogging and beatings to the point of

unconsciousness. The individuals reportedly

remain in prison.

55. An informed source reported that poet Mr

Sattar Sayyahi, died under suspicious

circumstances in November 2012 following his

release and subsequent threats by the Ministry

of Intelligence. Mr. Sayyahi’s uncle and

neighbour were also reportedly arrested,

interrogated and tortured, by the authorities

after they took Mr. Sayyahi to the hospital. The

interviewee maintained that Mr. Sayyahi’s uncle

and neighbour were questioned about their

conversations with him prior to his death. It

was further reported that authorities attacked

and arrested an estimated 130-140 funeral

attendants, including Mr. Sayyahi’s 17-year old

cousin, Ali Sayyahi’s, whose hand was reportedly

broken as a result of torture while in

detention.

2. Baloch

56. Sistan-Balochistan is arguably the most

underdeveloped region in Iran, with the highest

poverty, infant and child mortality rates, and

lowest life expectancy and literacy rates in the

country. The Balochi are reportedly subjected to

systematic social, racial, religious, and

economic discrimination, and are also severely

underrepresented in state apparatuses.[59] It

has also been reported that the linguistic

rights of the Baloch are undermined by a

systematic rejection of Balochi-language

publications and limitations on the public and

private use of their native languages, in

contravention of article 15 of the Iranian

Constitution, and article 27 of the ICCPR.

Moreover, the application of the Gozinesh

criterion, which requires state officials and

employees to demonstrate allegiance to Islam and

to the concept of velayat-e faqih (Guardianship

of the Islamic Jurist), further exacerbates

their socioeconomic situation, by limiting

employment opportunities.[60]

57. Accounts of the destruction of Sunni mosques

and religious schools, and allegations of the

imprisonment, and assassination of Sunni

clerics, have also been reported. Baloch

activists have reportedly been subject to

arbitrary arrests and torture. The

Sistan-Balochistan province experiences a high

rate of executions for drug-related offenses or

crimes deemed to constitute “enmity against god”

in the absence of fair trials.[61] Allegations

were also received that the Government has used

the death penalty as a means to suppress

opposition in the province.[62] In a plea to the

international community, the Balochistan

People’s Party reported that two Baloch

prisoners in Zahidan Prison were sentenced to

death following a demonstration in Rask City and

other towns in the Sarbaz area in May 2012.

Political prisoners in the detention center who

reportedly protested against the death sentences

were punished with exile.[63]

58. It was also reported that netizen Abdol

Basit Rigi and political activists Abdoljalil

Rigi and Yahyaa Charizahi were charged with

“enmity against God”, and sentenced to death

following forced confessions. One of the

political prisoners, Abdol Basit Rigi, was

arrested three years ago, reportedly kept in

solitary confinement for eleven months, and

allegedly tortured. It is further reported that

two of the activists were transferred to

solitary confinement in the Intelligence

Ministry two days before their execution, where

they were subjected to violent torture and

forced to record a televised confession.[64]

H. Religious minorities

59. The Special Rapporteur remains deeply

concerned about the human rights situation

facing religious minorities in Iran. Reports

from and interviews with members of the Bahai,

Christian, and Sunni Muslim communities continue

to portray a situation in which adherents of

recognised and unrecognised religions face

discrimination in law and/or in practice. This

includes various levels of intimidation, arrest

and detention. A number of interviewees

maintained that they were repeatedly

interrogated about their religious beliefs, and

a majority of interviewees reported being

charged with national security crimes and/or

propaganda against the State for religious

activities. Several interviewees reported that

they were psychologically and physically

tortured.

1. Baha’is

60. In its comments on the Special Rapporteur’s

report to the 67th session of the General

Assembly, the Government asserted that despite

the fact that the Baha’i faith is not a

recognised religion in the country, its

followers have equal rights under the law, and

that they may not be prosecuted or imprisoned

for adhering to their beliefs. However, it was

also maintained that propagation of the Baha’i

faith is in “breach of the existing laws and

regulations” and that activities that constitute

its proselytisation disrupt public order and may

be limited in accordance with Article 18 and 19

of the ICCPR. However, the Human Rights

Committee emphasises that the teaching of

religious beliefs are protected and that “the

practice and teaching of religion or belief

includes acts integral to the conduct by

religious groups of their basic affairs, such as

the freedom to...establish seminaries or

religious schools and the freedom to prepare and

distribute religious texts or publications.”

61. It has been reported that 110 Baha’is are

currently detained in Iran for exercising their

faith, including two women, Mrs. Zohreh Nikayin

(Tebyanian) and Mrs. Taraneh Torabi (Ehsani),

who are reportedly nursing infants in prison. It

was further estimated that 133 Baha’is are

currently awaiting summonse to serve their

sentences, and that another 268 Baha’is are

reportedly awaiting trial. Authorities

reportedly arrested at least 59 members from

August to November 2012, some of whom have been

released. Several sources reported that since

October 2012, authorities have raided the homes

of at least 24 Baha’is and arrested 25

individuals in the city of Gorgon and its

surrounding provincial areas, 10 of whom

remained in custody at the time of drafting this

report. It has also been reported that Baha’is

in the northern city of Semnan have been the

focus of escalating and broad persecution over

the last three years. Baha’is in this city have

allegedly faced physical violence, arrests,

arson, and vandalism to their homes and grave

sites. The majority of Baha’i-owned businesses

in Semnan and the northern city of Hamadan have

reportedly been closed. [65]

62. Members of the Baha’i community are reported

to continue to be systematically deprived of a

range of social and economic rights, including

access to higher education. Informed sources

have reported that authorities from three

different universities expelled five Baha’i

students in November 2012. Four of these

students were reportedly offered continued

admission if they denied and/or pledged to

abandon their religious practices. The students

were reportedly expelled for refusing the offer.

2. Christians

63. The Government stressed that “[r]ecognition

of Christianity, by the Constitution … does not

constitute judicial immunity” for its

followers.[66] The Special Rapporteur asserts

that Christians should not face sanctions for

manifesting and practising their faith, and

therefore remains concerned that Christians are

reportedly being arrested and prosecuted on

vaguely-worded national security crimes for

exercising their beliefs.

64. Sources have reported that at least 13

Protestant Christians are currently in detention

centres across Iran, and that more than 300

Christians have been arrested since June 2010.

Those currently in prison include Pastor Behnam

Irani and church leader Farshid Fathi, who are

both serving six-year sentences on charges such

as “acting against national security”, “being in

contact with enemy foreign countries,” and

“religious propaganda.” Sources maintain that

the evidence used against Mr. Fathi was related

to his church activities, including distributing

Persian-language Bibles and coordinating trips

for church members to attend religious seminars

and conferences outside the country. Several

Protestant churches with majority Assyrian or

Armenian-speaking congregations have also been

forced to cease Persian-language services, and

it was recently reported that the Janat Abad

Assemblies of God Church in Tehran, which held

all-Persian services, was shut down on 19 May

2012.[67]

65. The Special Rapporteur is also concerned

that the right of Iranians to choose their faith

is increasingly at risk. Christian interviewees

consistently report being targeted by

authorities for promoting their faith,

participating in informal house-churches with

majority convert congregations, allowing

converts to join their church services and

congregations, and/or converting from Islam. A

majority of interviewees that identified

themselves as converts reported that they were

threatened with criminal charges for apostasy

while in custody, and a number of others

reported that they were asked to sign documents

pledging to cease their church activities in

order to gain release.

3. Dervishes

66. Interviews and information submitted to the

Special Rapporteur continue to allege that

Gonabadi Dervishes, who are Shia Muslims, are

subjected to attacks on their places of worship,

and are arbitrarily arrested, tortured, and

prosecuted. Sources note that 12 Gonabadi

Dervishes remained in official custody as of

November 2012, including four lawyers, Farshid

Yadollah, Amir Eslami, Omid Behroozi, and

Mostafa Daneshjoo. It was further reported that

on 12 December 2012 six dervishes from the city

of Kovar were tried in a revolutionary court in

Shiraz, some for the capital offence of

Moharebeh.

4. Other faith groups and spiritual practices

67. Representatives of the Yarsan, a religious

minority active amongst Kurdish Iranians,

reported that their religious gatherings are

routinely repressed. Additionally, the leader of

the Yarsan, Mr. Seyyed Nasradin Heydari, is

allegedly under house arrest. Yarsan who pass

university entrance exams and profess that they

practice the Yarsan faith are purportedly

refused admission. Moreover, the Special

Rapporteur is also concerned about reports

regarding the arrest of leaders of spiritual,

semi-spiritual, and meditation groups in Iran.

For example, sources report that Peyman Fattahi,

leader of the spiritual community of the

El-Yasin, was detained for almost three weeks in

October and November 2012.

I. Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender

community

68. The Special Rapporteur continues to share

the concern of the Human Rights Committee that

members of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and

transgender community (LGBT) face harassment,

persecution, cruel punishment, and are denied

basic human rights. The new draft Islamic Penal

Code criminalises same-sex relations between

consenting adults. Articles 232-233 of the new

Penal Code would mandate a death sentence for

the “passive” male involved in sodomy,

regardless of whether his role was consensual.

Under the new law, “active” Muslim and unmarried

males may be subject to 100 lashes so long as

they are not engaged in rape. Married and/or

non-Muslim males may be subject to capital

punishment for the same act. Men involved in

non-penetrative same-sex acts or women engaged

in same-sex acts would also face 100 lashes

according to the new Penal Code.

69. The Special Rapporteur is concerned that

criminalising same-sex relations could lead to

violation of core human rights guarantees,

including the right to life, the right to

liberty, the right to be free from

discrimination as well as the right to be

protected against unreasonable interference with

privacy, provided under international human

rights instruments, particularly the

International Covenant on Civil and Political

Rights. The Special Rapporteur joins the United

Nations Secretary-General and High Commissioner

for Human Rights in her call for ending violence

and discrimination against all people,

irrespective of their sexual orientation and

gender identity.[68]

70. Interviews with 24 members of the Iranian

LGBT community for this report reinforce many of

the concluding observations forwarded by the

Human Rights Committee’s periodic review of

Iran. Fifteen interviewees believed that they

were arrested at least once for their sexual

orientation or for associating with other LGBT

persons. Thirteen reported that once in

detention, security officers subjected them to

some form of torture or physical abuse;

including punches, kicks and baton strikes to

the head or body and, in a few cases, sexual

assault and rape. Several people reported that

they were coerced into signing confessions.

Iran’s criminalisation of same-sex relations

facilitates physical abuse in the domestic

setting as well. A majority of these individuals

reported that they were beaten by family members

at home, but could not report these assaults to

the authorities out of fear that they would

themselves be charged with a criminal act.

J. Socioeconomic rights

1. Right to education

71. In addition to limitations placed on access

to education for women and some religious

minorities, reports continue to maintain that

students engaged in political activities are

being deprived of their education. In a letter

to the Special Rapporteur, the Human Rights

Commission of Daftar Tahkim Vahdat an Iranian

Student Organization stressed the increase in

punitive action in reaction to peaceful efforts

by students to improve academic life and defend

student and human rights, vis-à-vis student

organisations, publications, and activism.

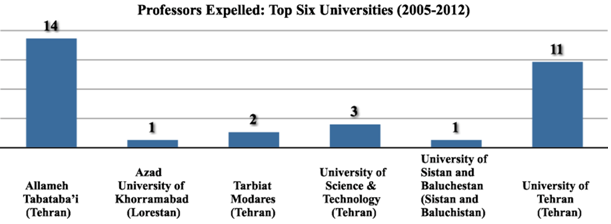

72. Citing statistics based on information

gathered from news sources, the Commission

maintains that since March 2005, there have been

at least 935 cases of students deprived from

continuing education for either one or more

semesters, and at least 41 cases of professors

expelled from university. Of the 976

aforementioned reported cases, more than 140

cases apply solely to Allameh Tabataba’i

University (14 professors and 57 students),

headed by Mr. Sadreddin Shariati, and Amirkabir

Polytechnic University of Tehran (72 students),

headed by Mr. Alireza Rahaei. Moreover, three

student publications or associations have been

forcibly closed.

73. Individuals interviewed for this report

maintained that they were denied access to

universities despite achieving top scores on

university entrance exams for higher degrees as

a result of their political activities. One top

ranking political science student, for example,

reported that he/she was denied entrance to a

Masters degree program until he/she signed a

pledge that he/she would abstain from student

activism for the duration of his/her studies.

However, he/she was later denied access to PhD

studies and alleged that he/she had been

informed that the Ministry of Intelligence had

placed him/her on a list of students that were

banned from continuing their education.

74. The Special Rapporteur is also concerned

over allegations that university professors in

the field of humanities continue to be expelled

for their views. Minister of Science and

Technology, Mr. Kamran Daneshjoo, reportedly

asserted that professors uncommitted to

Velayat–e Faqih (Guardianship of the Islamic

Jurist), or who have a “secular or

liberal-democracy point of view” are not needed

in Iran.[69] One professor reported that he/she

was subjected to immense pressure from the head

of his/her university to prove his/her devotion

to Islamic values and the Iranian State by

demanding that he/she join daily prayers at the

university. Refusal to cooperate was reportedly

followed by death threats from the Ministry of

Intelligence, which informed him/her that if

he/she refused to cooperate with the Islamic

guidelines of the university he/she would be

“expelled, killed, and buried in an undisclosed

grave”. The professor further reported that

twelve colleagues had been expelled or forced

into early retirement for alleged

non-cooperation with Islamic guidelines of the

university in the last five years alone.

2. Economic sanctions

75. The Special Rapporteur joins the

Secretary-General in continuing to express

concern at the potentially negative humanitarian

effect of general economic sanctions imposed on

the Islamic Republic.[70] The Committee on

Economic, Social and Cultural Rights makes clear

that sanctions do not nullify a State Party’s

obligations under the International Covenant on

Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.[71] The

Committee also noted that “the inhabitants of a

given country do not forfeit their basic

economic, social and cultural rights by virtue

of any determination that their leaders have

violated norms relating to international peace

and security”. They further stated that the

imposition of international sanctions does not

in any way nullify or diminish the obligations

of a State party to ICESCR to do its utmost to

ensure that every individual, without

discrimination, enjoys rights stipulated by the

Covenant; and to seek measures to protect

vulnerable groups.

76. Furthermore, the Committee makes clear that

imposing sanctions bestows obligations upon the

imposing parties to respect the economic and

social rights of the sanctioned country’s

population.[72] Principles introduced in a 1995

non-paper on the humanitarian impact of

sanctions to the Security Council, by its five

permanent members calls for “unimpeded access to

humanitarian aid” within the targeted country

and for monitoring the humanitarian effects of

sanctions, while a 1998 letter to the Council

from the Secretary-General urges sanctions

regimes to account for human rights and

humanitarian standards.[73]

77. The Special Rapporteur takes note of efforts

by parties imposing sanctions, including through

“humanitarian exemptions” to exempt foodstuffs,

medical supplies, and other humanitarian goods

from the sanctions. However, reports of drug

shortages used in the treatment of illnesses

such as cancer, heart disease, haemophilia, and

multiple sclerosis gives rise to concerns that

such exemptions are potentially not meeting

their intended purpose.[74] In light of these

reports, the Special Rapporteur remains

concerned about the efficacy of international

safeguards meant to reduce the adverse impact of

general sanctions on the Iranian population. He

will therefore continue to seek the cooperation

of the Iranian Government, as well as those of

sanctions-imposing countries to effectively

report on the efficaciousness of humanitarian

safeguards.

78. Some reports point to sanctions aimed at

Iran’s financial sector, which could pose an

impediment to conducting transactions for

exempted items despite humanitarian waivers.[75]

The Special Rapporteur is further concerned by a

serious rise in inflation, increased commodity

prices, and subsidy cuts, which could also

hinder access to essential goods.[76] Some

reports also indicate that domestic authorities

could take steps to mitigate some humanitarian

effects of sanctions and better meet obligations

under the International Covenant on Economic

Social and Cultural Rights.

79. The Special Rapporteur stresses that further

investigation into these issues is necessary,

and requests the assistance and cooperation of

the Government in facilitating an unfettered

visit to the country in order to adequately

assess the humanitarian consequences of

sanctions and their impact on economic and

social rights of Iranians. He also appeals to

relevant UN agencies and sanctions-imposing

Governments to aid in the evaluation of the

impact of sanctions on Iran’s general

population.

III. Conclusions and Recommendations

80. In reflecting on the last two years of his

mandate and his current report, the Special

Rapporteur concludes that there has been an

apparent increase in the degree of seriousness

of human rights violations in the Islamic

Republic of Iran. Frequent and disconcerting

reports concerning punitive State action against

various members of civil society, reports about

actions that undermine the full enjoyment of

human rights by women, religious and ethnic

minorities; and alarming reports of retributive

State action against individuals suspected of

communicating with UN Special Procedures raises

serious concern about the Government’s resolve

to promote respect for human rights in the

country.

81. The Special Rapporteur also continues to be

alarmed by the rate of executions in the

country, especially for crimes that do not meet

serious crimes standards, and especially in the

face of allegations of widespread and ongoing

torture for the purposes of soliciting

confessions from the accused. The Government’s

ability to meaningfully address matters raised

by a number of human rights instruments and the

Human Rights Council is constrained by a lack of

meaningful cooperation, by its intransigent

position on the existence of human rights

violations in the country, and by de jure and de

facto practices that undermine its international

and national human rights obligations.

82. The Special Rapporteur, therefore, proposes

that the Iranian Government undertake the

following actions in order to address the

preponderance of issues raised in this and

previous reports communicated by the expert:

(a) Extend its full cooperation to the country

mandate-holder by engaging in a substantive and

constructive dialogue and facilitating a visit

the country.

(b) Immediately investigate allegations of

reprisals against individuals that cooperate

with international human rights instruments and

organizations and to take measures to “ensure

adequate protection from intimidation or

reprisals for individuals and members of groups

who seek to cooperate or have cooperated with

the United Nations, its representatives and

mechanisms in the field of human rights”.4

(c) Desist from actions designed to injure or

intimidate those who work to identify human

rights violations, promote redress, and those

that may cooperate with international human

rights mechanisms.

(d) Consider the immediate and unconditional

release of civil society actors and human rights

defenders prosecuted for protected activities;

including journalists, netizens, lawyers and

student, cultural, environmental, and political

activists that work to promote civil, political,

economic, social and cultural rights currently

detained for activities protected by national

and international law.

(e) Expedite its voluntary commitment to

establish a National Human Rights Commission, in

accordance with Paris Principles.

(f) Examine and address those laws that

contravene its international obligation to

eliminate all forms of discrimination in law and

practice. These include those laws and policies

that undermine gender equality and women’s

rights, and that discriminate against religious

and ethnic minorities, and members of the

lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender

community in the country.

(g) Consider the immediate release of prisoners

of conscience such as Pastors Behnam Irani,

Farshid Fathi, as well as the leaders of the

Baha’i community, and fully honor its

commitments under Article 18 of ICCPR that

guarantee the right to freedom of thought,

conscience and religion, which was accepted by

Iran without reservation.

(h) Investigate all allegations of torture,

address impunity and end the culture of

investigation through confession as reflected by

the breadth of reports communicated to the

Special Rapporteur.

(i) Consider a moratorium on capital punishment

until the efficacy of judicial safeguards can be

meaningfully demonstrated, and stay the

execution of individuals who have alleged

violations of their due process rights.

(j) Improve transparency on the impact of

sanctions and report on measures it has taken to

protect its inhabitants from the potential and

actual negative impacts of such sanctions.

(k) The Special Rapporteur also calls on the

United Nations system and on sanctions-imposing

countries to monitor the impact of sanctions and

to take all appropriate steps to ensure that

measures, such as humanitarian exemptions, are

effectively serving their intended purpose to

prevent the potentially harmful impacts of

general economic sanctions on human rights.

[Read Full Annex]

[1] A/HRC/12/L.8; Cooperation with the United

Nations, its representatives and mechanisms in

the field of human rights, 25 September 2009

[2] http://www.daneshjoonews.com/node/8058;

http://af-express.com/1391/08/24/

http://hrdai.net/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=1064:-------3-----------&catid=5:2010-07-21-10-19-53

[3]

https://www.iranhumanrights.org/2012/12/kurdish_prisoners/;

http://persianbanoo.wordpress.com/2012/12/15/3-kurdish-political-prisoners-to-be-tried-on-charges-of-contact-with-un-special-rapporteur-ahmed-shaeed/;

http://hra-news.org/1389-01-27-05-27-21/14413-1.html;

[4] A/HRC/12/L.8; Cooperation with the United

Nations, its representatives and mechanisms in

the field of human rights, 25 September 2009

[5] Attached as addendum: “A Brief reply the

Report of the UN Special Rapporteur to the 22nd

session of the Human Rights Council”

[6] GC25, para 1.

[7] Art 2(1) & 25, ICCPR; GC25, paras 4, 6 & 17.

[8] GC25, para 7.

[9] CCPR/IRN/3, para 885. Constitution, Art 115;

GC25, para 15.

[10] GC25, para 17.

[11] A/HRC/WGAD/2012/30.

[12]

http://www.bbc.co.uk/persian/iran/2013/01/130117_ka_ejei_mosavi_karobi.shtml.

[13] GC25, para 20.

[14] GC25, para. 7.

[15] GC25, para 12.

[16]

http://www.farsnews.com/newstext.php?nn=13911019000569;

http://www.1000news.ir/1391/10/24/2074/;

http://www.farsnews.com/newstext.php?nn=13911023000070.

[17] http://cpj.org/imprisoned/2012.php

[18] http://cpj.org/imprisoned/2012.php

[19] See Annex: Journalist’s Cases Section

[20] See Annex: Human Rights Defender’s Cases

Section;

[21] Interview with the Office of the Special

Rapporteur, August 2012

[22]

http://www.iranhumanrights.org/2012/07/narges-mohammadi-hospitalized-in-prison/

;

http://amnesty.org/en/individuals-at-risk/narges-mohammadi

[23]

http://www.ibanet.org/Article/Detail.aspx?ArticleUid=8281ffa3-1ce7-4976-a93d-e488cc0fa333

[24]

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/10/03/world/middleeast/iran-engaged-in-severe-clampdown-on-critics-un-says.html?_r=0;

http://www.amnesty.org/en/news/iran-must-release-human-rights-defender-mohammad-ali-dadkhah-2012-10-01;

http://www.iranhumanrights.org/2012/12/dadkhah_lawyer/;

[25]

http://www.kaleme.com/1391/11/03/klm-130247/;

http://www.amnesty.org/en/news/iran-stop-cruel-charade-and-release-human-rights-lawyer-good-2013-01-23;